Signs and social status: signatures on Visigothic script charters (I)

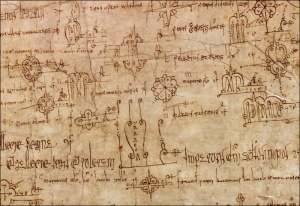

One of the most characteristic diplomatic elements on Visigothic script charters are the signature signs. But, which were the designs available and what did they mean?

On Visigothic script – and other medieval – charters preserved from the Iberian Peninsula it is very common to find a large list of individuals ratifying the legal act reported in each document within the validatio area (signature box). Before public notaries were institutionalised as legal agents of the written act in the early 13th century, ecclesiastical scribes were in charge of seeking guarantors of their text, a function that was developed by these signatures. In these lists, grantors and also witnesses of the documentary action, and sometimes even amanuenses, were referred to by name, title or profession, stating their role – what is called in diplomatics “written subscription” –, but, also, besides this information, sometimes they added one more thing: a sign – a “manual subscription” – which represented them.

While our signatures nowadays are fairly arbitrary, grantors, witnesses, and scribes did not decide their distinctive signs on a whim but rather designed them carefully: the type of sign they could use as a basic model was previously established by tradition, and, it seems that it also relied on their social status and the style preferred during each period. That being the case, what types of signs can be found? What do these signs tell us about their owners? How did designs change throughout the centuries?

Types of signs

There are two main types of signs used as signatures in medieval charters from the Iberian Peninsula: calligraphic signs and monogrammatic signs.

The calligraphic signs are the easiest and most generic type of signs. There are three types under the classification of calligraphic signs considering their design:

FIG. 1 Calligraphic signs type 1: lines and dots.

- those formed by a horizontal line, more or less developed, to which vertical strokes and/or dots were added [FIG. 1];

FIG. 2 Calligraphic signs type 2: crosses.

- those which look like a cross, that can be enclosed in a tetra petal form, or in a geometric form (circles or squares) [FIG. 2];

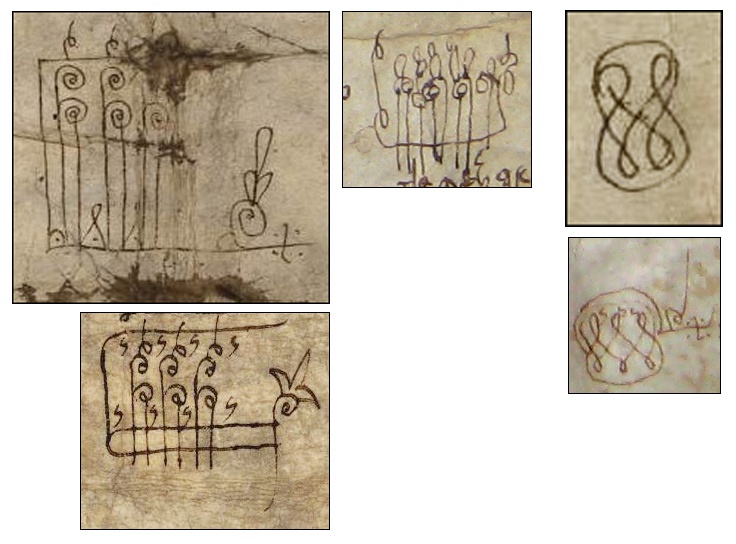

FIG. 3 Calligraphic signs type 3: subscripsi and ruche.

- and, those which represent the expression subscripsi, a medieval interpretation of the Late Roman Empire tradition of subscriptio with which the validatio ended. In the early Middle Ages, the word subscripsi was reduced, abbreviated to only three letters SSS, SCS, SUB. These abbreviations could be drawn in a still recognisable form (type a [FIG. 3 left]) or not (type b [FIG. 3 right]). In the latter twisted case, we call the sign “ruche”.

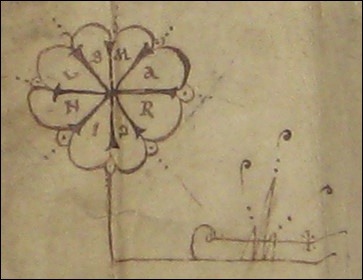

FIG. 4 Monogrammatic signs (Gudesteus, Hermiario, Amor).

The monogrammatic signs, on the other hand, refer directly to the specific person to whom they are attached in the subscription since their design is based on the name (in full or not) or the profession of the person who employed it [FIG. 4].

Types by geographical area

So, how frequent were these signs? In the northwestern Iberian Peninsula, signs were used in almost all the charters. But, in contrast, on the other side of the Iberian Peninsula, signs were not commonly used.

Within the Catalan and Aragonese documentation, drawing a sign following the subscription of witnesses and grantors in charters was unusual. And when they were used, it seems that the cross-like signs were the type preferred – as was also the case in French charters – instead of the other calligraphic models or the monogrammatic signs, and that these crosses were only employed by people linked to the ecclesiastical world and by kings. In the Astur-leonese area though, the world of signs was different.

Types by century

Looking at a corpus, it can be seen how the preference for one or another design changed over time. The calligraphic signs seem to be the oldest type of signs used since they were already drawn in the earliest preserved charters while the monogrammatic signs were not used until the second half of the 10th century.

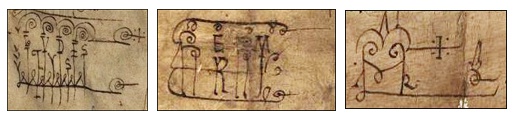

Moreover, the cross-shaped signs with geometric form and the subscripsi signs within the calligraphic type were the oldest; the latter being more frequent during the 10th century. In the 11th century, the calligraphic signs, and especially the cross-shaped ones without being enclosed in any form, were the favourite. In the 12th century, however, the preferred style changed significantly to the monogrammatic type [FIG. 5, 6, 7].

Types by social status

The use of one design or another for the signature signs seems to vary considering who used them and to whom were they linked.

The signs formed by a long horizontal line with vertical strokes added or with cross-like form were generally used as signatures of laity, both by grantors – very frequently – and witnesses. Thus, this type of sign was not only used by those who we can suppose to be illiterates, who signed by adding a dot or a line. The signs formed by a cross enclosed by a tetra petal were widely used too, although they were seldom used by bishops or abbots. The cross-like signs enclosed by a geometric figure, rarely in a square, were chosen by laity, and, particularly, by the grantors of the document.

The signs called “ruche” were most commonly used by bishops, priests, and scribes.

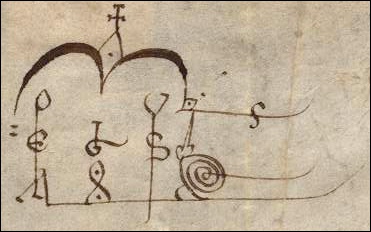

Finally, the signs derived from subscripsi, in the less cursive form, decorated with loops and sometimes explicitly including three SSS above, were, by comparison with other types of signs, overwhelmingly used as the favourite symbols for kings, bishops, abbots, judges and scribes.

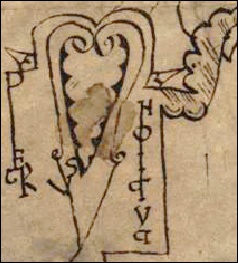

FIG. 5 Pelagius, judge (1105-1128).

Therefore, it is significant to realise that all the grantors or witnesses who used this subscripsi sign instead of the cross-like forms belonged to the ecclesiastical hierarchy or were members of the royalty or noblemen. The higher social classes of the northwestern Middle Ages Iberian Peninsula, preferred this type of sign within the calligraphic ones to represent them. They were the cultivated group of the population, the ones capable of writing or paying a scribe to take the time and effort to design their personal sign.

FIG. 6 Petrus, presbiter (1110).

In contrast, the less cultured people, who were unable to write or not important enough to need the marketing provided by a fashionable personal sign used dots or lines to evidence their presence while the legal act of the written document took place. But, that was only in the 10th and 11th centuries, while the monogrammatic sign was taking shape. In the 12th century, this tendency changed.

FIG. 7 Martinus, personal notary of queen Urraca (1105).

Analysing the social status of the people who used this type of sign, it can be seen how 12th century scribes and other ecclesiastical dignities of the highest level, as well as some noblemen, chose to add their names, thus creating their own personal monogrammatic signature, while the subscripsi signs were kept as the signs of the kings, although not for long. Also, it must be highlighted that the monogrammatic signs evolved throughout the 12th century, their designs being progressively more complicated and personal, showing, in some cases, features that remind us of the ornamentation or miniatures of medieval manuscripts.

In the next post, I will discuss who wrote these signs and why it was important for their owners to have a distinctive personal sign.

>>> Read the 2nd part <<<

by A. Castro

[edited 12/07/2018]

Joan Vilaseca

Fantastic post! A direct window to early medieval mundane simbology in north-western iberian peninsula… Maybe those ‘personal’ signs were sometimes transmitted within families, as was customary for names? Well, that’s a question for your next post probably, but I could not resist…